Clinical Significance of WHO Classification and Cell Kinetic Study using PCNA and Ki-67 on Thymic Epithelial Neoplasms

|

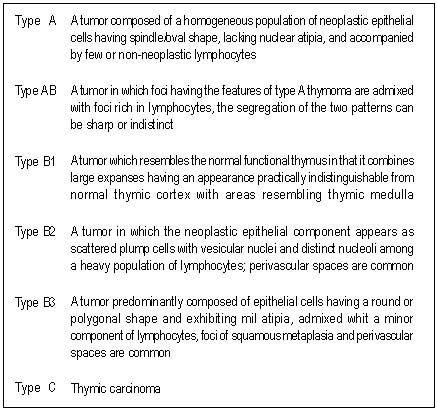

| Table 1. The definition of WHO classification of thymic epithelial tumors |

Condensed abstract

Cell kinetic study to evaluate if there is a correlation

between proliferation indices(PI) of the neoplastic thymic cells and

histological type with stage and OS.

|

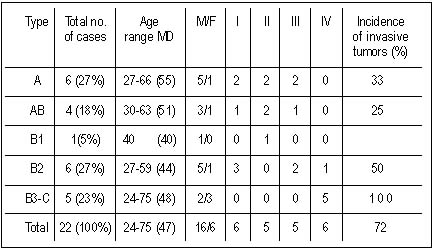

| Table 2. Clinical stage and the incidence of invasive tumors according to WHO classification |

Abstract Purpose

Thymic epithelial neoplasms(TEN) are rare tumors in

which the importance of histology is controversial. We performed cell

kinetic study to evaluate if there is a correlation between

proliferation indices(PI) of the neoplastic cells and histological type

with stage and OS.

|

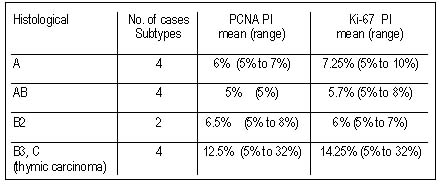

| Table 3. Correlation between PCNA and Ki-67 labeling indices and histological subtypes |

Patients and methods

Retrospective study of patients diagnosed with

TEN(1988–2000). Demographic and clinical variables and complete

follow-up data were obtained. PI using PCNA and Ki-67 were analyzed.

Results. We studied 22 patients. Median age was 47 years(range

24-75). Histological classification: type A=6(27%), AB=4(18%),

B1=1(4.5%), B2=6(27%), B3-C(thymic carcinoma)=5(23%). Invasive tumors

were seen in 72.72% of cases. Although the mean values of PCNA and Ki-67

were higher in types B3-C(12.5% and 14.25%) than in types A-B1-B2(5.8%

and 6.1%), there was no association with histological type. An

association among histologic type (A-AB-B2 vs B3-C) and stage (I-II-III

vs IV; p=0.001) was found. A complete resection was achieved in 74% of

cases. Complete remission was achieved in 18/21 patients who received

definitive treatment. There were 6(28.6%) perioperative deaths and 3

patients relapsed. Five-year DFS for patients with B3-C was 40% compared

with 100% for other subtypes. The actuarial 5-year OS of patients with

B3-C was 80%, whereas that of patients with other types was 88%.

Stage(p=0.001) and histology B3-C(p=0.008) were the only significant

variables in predicting recurrence. Stage IV (p=0.005) and age>

60years (p=0.03) increased the risk of death.

Discussion. The clinical behavior of TEN depends on stage and

histology. There was no correlation between PI and stage or histology. A

larger study is warranted.

|

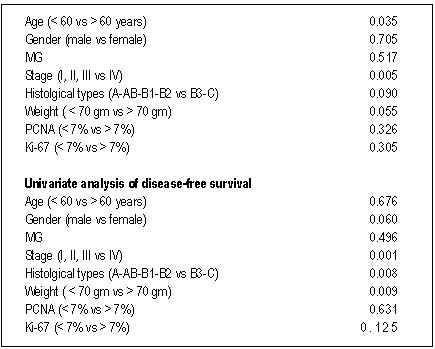

| Table 4. Univariate analysis of survival |

Introduction

Several classification systems for thymic epithelial

neoplasm (TEN) are currently in use.1-5 The low incidence of these

neoplasms and the lack of uniformity in the reported series made

necessary the unification of criteria thus resulting in the World Health

Organization (WHO) classification.6 A critical issue is the confuse

nomenclature of these classifications and an absence of consensus

regarding their prognostic value. Nowadays the most important predictive

factors for outcome still are complete resection7 and stage according

to Masaoka classification8 (I: totally encapsulated, II: invasion

through capsule, III: invasion into organs -pericardium, lung, great

vessels-, IVa: pleural or pericardial implants and IVb: hematogenous

metastasis).

Efforts have been made to discover immunohistochemical markers that

identify factors of poor prognosis9-11. Few studies have attempted to

correlate the proliferation index (PI) with the histological type12.

Cellular cycle is complex and some proteins are expressed exclusively in

the phases in which they intervene and their presence can reflect the

PI of the cell. Monoclonal antibodies directed against them have been

developed allowing to study two groups of proteins: those acting on DNA

synthesis during S-phase like PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear

antigen)13 and those expressed in proliferating but not resting cells

like Ki-6714,15. These methods have shown that in some neoplasms high

proliferative rates correlate with poor prognosis. These data correlate

with those obtained by flow cytometry16.

|

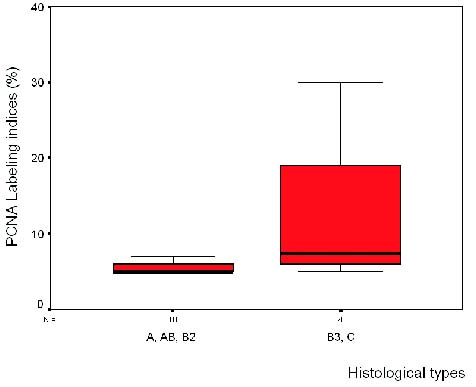

| Figure 1. PCNA labeling indices vs histological types. There was no difference between the other histoloical types |

Patients and Methods

Patients. Patients diagnosed with TEN in our institution

between 1988 and 2000 were included in the analysis. Age, gender,

clinical presentation, association with MG, stage, treatment, and

complete follow-up date were obtained from clinical records.

Histological classification. Analysis of tissue samples and

classification according to the WHO classification was carried out by a

pathologist (AG) in a blinded fashion. TEN were divided in four groups

depending on their nuclei characteristics (type A: spindle/oval shape,

type B: dendritic or epitheloid appearance). Tumors combining both

morphologies were designated as type AB, and type C (atypia and

necrosis). Type B tumors were further subdivided into three categories

(B1, B2 and B3) on the basis of the proportional increase in the

epithelial component and cytologic atypia. (Table 1)

Immunohistochemistry. Studies were performed on paraffin embedded

tissue sections in 14 cases using monoclonal antibodies directed against

PCNA and Ki-67 (Dako, Carpinterra, CA) in an automated immunostaining

equipment (Ventana, Nexes, Tucson, AZ) as suggested by the manufacturer.

Labeling index was determined by light microscopy with an oil-immersion

objective randomly counting 500 tumor epithelial cells and expressing

the results as a percentage of positive cells.

Statistical analysis. Cross-tabulation between present status and

clinical variables (age, gender, presence of MG, tumor weight, invasion,

stage, histological type and PI using PCNA and Ki-67) were used to

screen for significant associations using the Chi-square test for

independence. The correlation between PCNA and Ki-67 labeling indices

was carried out using the Spearman correlation test. Overall survival

(OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) curves were plotted according to

the method described by Kaplan and Meier and analyzed using the log-rank

test. A p value was considered significant if it was below 0.05. The

analysis was performed using the SPSS-10 commercial software package.

Results

Clinical presentation and diagnostic methods. Twenty-six patients

were diagnosed with TEN between 1988 and 2000. Four were excluded

because of incomplete data. Sixteen patients (72%) male and 6(28%)

female were included. Male-to-female ratio was 2.6:1. Mean age was 50.5

years (range 24-75). Sixteen patients (72%) had symptoms of MG at onset,

2(9%) presented with symptoms attributable to anterior mediastinal mass

(i.e. shortness of breath and chest pain), 1 patient (4.5%) had

disautonomia at onset and in 1(4.5%) the diagnosis was preceded 12

months by pure red blood cell aplasia. The tumor was discovered on

routine chest radiograph in 2(9%) patients. No other paraneoplastic

syndromes were found. According to Masaoka classification there were 6

patients in stage I, 5 in stage II, 5 in stage III and 6 in stage IV.

Histological diagnosis was made in material obtained using fine-needle

aspiration (4.5%), core biopsies (9%) or surgical resection (86.5%).

According to WHO classification 27% were type A, 18% AB, 4.5% B1, 27%

B2, and 23% B3-C types (Table 2).

The computed tomography (CT) was abnormal in all cases, suggesting an

invasion that was proved by histological studies in 16 of them (72%

sensitivity and 100% specificity). When invasive TEN were analyzed we

found necrosis in 9/16 patients (56%; p<0.05) and mediastinal

lymphadenopathy in 11/16 patients (69%; p<0.05).

Mean tumor weight was 70 grams (range 30–100) and mean diameter was

8.5 cm (range 3.5–15.1). There were no differences between invasive and

no invasive TEN in weight (< 70 vs. > 70 gr.; p=0.09) or diameter

(< 8.5 vs. > 8.5 cm.; p=0.6).

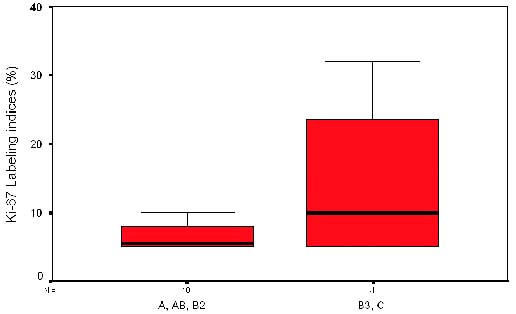

Determination of PCNA and Ki-67 labeling indices. Although mean

values of both PI were higher in types B3-C (stage IV) as compared to

types A-AB-B2 (Table 3 and figures 1 and 2), there was no association

between levels of PCNA and Ki-67 (<7% vs. > 7%) and histological

type (A-AB-B2 vs B3-C; p=0.099; p=0.48 respectively). The patients who

relapsed showed higher PI (mean PCNA=12.5%; mean Ki-67=14.25%) than

those who did not relapsed (PCNA=5.83% and Ki-67=6.31%), although the

difference was not statistically significant. The Spearman’s correlation

coefficient between PCNA and Ki-67 was 0.389. An association among

histological type (A- AB-B2 vs B3-C) and stage (I-II-III vs IV)

(p=0.001) was found.

|

| Figure 2. Ki-67 labeling indices vs histological types. Thymic carcinoma showed higher labeling indices by ki-67 antibody compared with the A-AB-B2 but there were no significant differences. |

Treatment and results

Complete resection was achieved in 16(74%) patients,

partial resection in 5(23%) and 1(4.5%) was solely biopsed. The approach

was medial sternotomy in 19 cases (86.71%) and in 2 cases (9.52%) it

was posterolateral thoracotomy. Ten (45%) patients required resection of

pericardium or lung. In this series 16(72%) patients presented with

symptoms of MG. After definitive resection 8 (50%) patients remained

asymptomatic, 7(44%) had partial improvement and 1(6%) did not respond. A

patient develop gastric non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma 4 years after the

thymoma diagnosis.

The mean follow-up was 58 months (range 12–228). Six patients (27%)

received postoperative radiotherapy in doses varying from 40 to 60 Gy

(complete resection=1 and partial resection=5). Of these 3(13.5%) had

stage III (type A=1 and B2=2) TEN, and 3(13.5%) had stage IV thymic

carcinoma. One patient did not accept treatment (stage IVa, B2) and is

alive 24 months after diagnosis. Of the 21 patients who received

definitive treatment, 18 achieved complete remission. Of these 12

(54.5%) were alive without relapse at last follow-up. There were

3(13.5%) perioperative deaths (2 stage II and 1 stage IV) due to

myasthenic crisis, 3(13.6%) patients died of unrelated causes. Three

patients (13.5%) relapsed during the follow-up period (B3=2, C=1) at 41,

61 and 24 months respectively. The relapse site was lung in 2 patients

and retroperitoneum in 1. In all cases complete resection was possible.

Two patients are disease-free at 12 and 18 months and the other

developed a new recurrence 5 months after resection and is currently

being treated with chemotherapy.

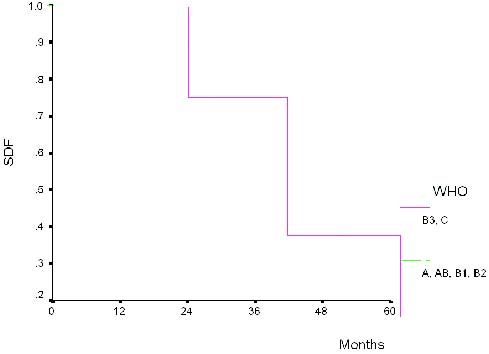

The recurrence probability of TEN was 51% at 24 months and 40% at 60

months. When A-AB-B2 and B3-C groups were compared, 5-year DFS was 100%

and 40% respectively. On univariate analysis only stage (I, II, III vs

IV; p=0.001) and histological classification (A, AB, B1, B2 vs B3 and C;

p=0.008) were of value for the prediction of recurrence(Figure 3).

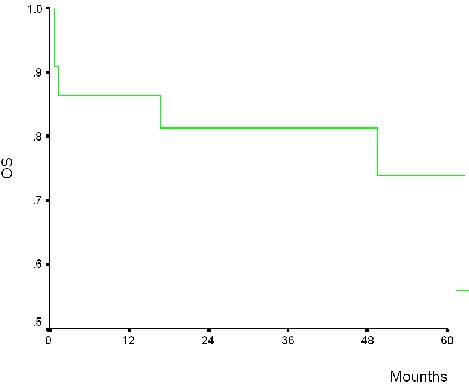

The actuarial 5-year survival rate for the entire group was 86%. For

patients with type B3-C it was 80% at 5 year, whereas for patients with

other types it was 88%. On univariate analysis both stage IV (p=0.005)

and age > 60 years (p=0.03) were risk factors for death(Table 4).

Histology (A-B1-B2 vs. B3-C) was correlated with stage (I-II-III vs IV,

p=0.001). The actuarial 5-year survival rate according to Masaoka

classification was: stage I=100%(6/6), II=60%(3/5), III=100%(5/5) and

IV=83.3% (5/6)(Figure 4).

Discussion

Higher absolute values of PCNA and Ki-67 expression was

found in types B3-C than in types A, AB, B1, B2 TEN, thus reflecting a

low growth proliferation in non-invasive or minimally invasive thymic

epithelial neoplasias, although no statistically significant differences

were observed.

In the reported series of TEN male and female patients16 are equally

affected and 70% of cases occur during the sixth and seventh decades of

life (mean age 53)17. In our series we found a slight male

predominance(male-to-female ratio 2.6:1) and patients were younger(mean

age 47). We also found a high prevalence of associated systemic

syndromes and incidental finding was made only in 9% of our patients in

contrast to other published data in which this occurs in 40 to 50% of

patients18.

Imaging studies play an important role in the detection and staging of

TEN. CT is the method of choice in the evaluation of a mediastinal mass

with a 72% sensitivity and 100% specificity for invasive TEN. CT can

differentiate cystic from solid lesions and the presence of fat or

calcium within the lesion. The findings suggestive of invasion include

necrosis and mediastinal lymphadenopathy as well as obliteration of

mediastinal fat planes or poor demarcation of tumor from adjacent

structures. Baron et al19 showed that in patients with proven thymomas,

the CT showed an ovoid soft-tissue density mass in the anterior

mediastinum and necrosis in 100% of patients. An important consideration

to be made is whether the lesion determines the treatment plan.

Prognostic factors that have been associated with better survival

include non-invasion, lower stage and complete surgical resection.

Invasion is reported in 30% to 40% of the patients8. Bernatz et al.18

demonstrated an overall 15-year survival rate of 12.5% in the invasive

group and 47% in the non invasive group. Several studies have examined

the effect of the extent of surgical resection on OS and DFS. In 241

operative cases, Maggi and colleagues20 found an 82% OS rate in those

patients whose tumors underwent complete resection and 26% survival rate

at 7 years in those undergoing biopsy alone. Yagui et al21 reported

excellent long-term survival with extended resection in patients with

stages III–IV. Their overall 5- and 10-year survival rates were 77% and

59%, respectively. Ten out of 12 patients who underwent resection of the

superior vena cava had a long term survival without evidence of

recurrence. Nakahara and coworkers22 have shown that the survival rate

in patients with stage III disease undergoing complete resection was

comparable to those patients with stage I and II disease. Therefore,

regardless of stage, tumor resection is one of the import predictors of

treatment outcome. The Masaoka stage is also a prominent prognostic

factor8. Stages I-II can be considered together as a group with a

favorable prognosis; stages III-IV have a significantly worse prognosis.

In general, complete resection rate is about 70%, in nearly all stage

I-II and in 27%-44% of stage III patients14. In this series the complete

resection rate was 71% (stage I-II: 100%, stage III-IV: 40%) which does

not differ from published data.

Most TEN are slow-growing tumors and at diagnosis they present with a

high tumor volume, the mean diameter in this series was of 8.5 cms.

Caruso et al24 reported a mean diameter of 9.9 cm. Some authors suggest

that recurrence rate seem to be related to the size and stage of TEN. No

recurrence was observed if the tumor was less than 5 cm in diameter and

a recurrence rate of 15% and 33% was observed if the tumor diameter was

5–15 cm and more than 15 cm. resepectively25. In our series this fact

could not be confirmed but perhaps this is due to the number of patients

studied.

When TEN was suspected and the preoperative evaluation suggested a

resectable tumor, the surgical approach was medial sternotomy (86%),

which provides a wide exposure of the anterior mediastinum26. Previous

reports yielded an approximate 25% of invasive tumors.

In our series we found 22.3% non invasive and 72.7% invasive tumors.

These percentages were higher than reported because carcinomas (22.72%

in our series) were included in the analysis. Difference between these

data and previously reported data is due to the fact that in previous

reports carcinomas were not included. Using the WHO classification

Okumura et al reported 53.6% of invasive tumors (12.14% of which were

carcinomas)27. These data does not differ to much from ours.

The TEN are biologically heterogeneous tumors as it is demonstrated

by their association with paraneoplastic syndromes28. We found a higher

than expected prevalence of MG (72%), probably because our institution

is a national referral center for complex diseases. Improvement in

myasthenic symptoms is almost always recognized following thymectomy,

and complete remission rates varies from 7% to 63%1. In our series it

was 50%. The prevalence of association with MG in reference to Masaoka

classification was higher among stages I-II (100%) than among stages III

(60%) and IV (66%), but no significant difference in survival was noted

between patients with invasive and noninvasive thymomas.

Currently, death after TEN resection in the perioperative period is

rare and should be less than 6%29. In this series 3 deaths (13.6%)

occurred, all of them in patients with poorly controlled MG and

respiratory complications. Modern preoperative preparation, intensive

care facilities and plasmapheresis have reduced this risk.

Verley and Hollman2, Maggi and colleagues20 and Lewis and co-workers3

did not find a significant difference in the prognosis of patients with

and without MG. In the present study patients without MG had a higher

survival rate (100%) than patients with MG (84%), although difference

was not significant. The presence of MG may even confer a survival

advantage, but this may be due to a predominance of incidentally

discovered early-stage tumors in myasthenic patients.

Some authors consider the use of radiotherapy in all patients after

either a complete or partial surgical resection and even as primary

treatment29. In this series 27.3% received postoperative radiotherapy

with adequate local control. In 10/11 cases in stages III-IV, complete

remission was achieved without adjuvant therapy. These data demonstrate

that the most important factor predicting outcome is the complete

resection of the tumor. In patients who have residual macroscopic

disease, radiation therapy achieves local control in 60% to 90% of cases

regardless the stage. Three (13.6%) patients had distant relapses,

similar to the reported 9-11%30. The actuarial 5-year survival rate was

86% in our series.

|

| Figure 3. Disease-free survival for patients with types A-AB-B1-B2 and B3-C |

Our results differ from those reported in regard to age,

male-to-female ratio, association with MG, proportion of thymic

carcinomas and OS rate. These differences cannot be explained only by a

selection bias and they could show great variability in cell

composition, histologic grow patterns and different biological behavior

in our population. However, since this is the only study carried out in

our country, we cannot fully support this notion.

We examined the clinical significance of histologic classification of

TEN proposed by WHO. We analyzed separately the group of malignant

thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Seventy-seven percent of cases were types

A-AB-B1-B2. The higher proportion corresponded to types A and B2 (35.2%)

and the less frequent was the B1 (4.55%). MG was associated to type

A-AB-B1-B2 in 66.6%, 75%, 100% and 100% respectively. We found thymic

carcinoma in 23% of cases, all in stage IV. The mean age in these

patients was 48 years, similar to previously reported31. We did not

found correlation between stage and invasion with PI.

Although TEN have been traditionally separated into benign and

malignant categories, a reliable distinction cannot be made on the basis

of either histopathologic or electron microscopic findings. Malignancy

can only be demonstrated by the finding of invasion of the tumor capsule

or surrounding organs, or by the presence of metastasis31.

The traditional classification based on invasiveness, number of

lymphocytes and epithelial cell architecture is descriptive but

straightforward and based on numerous clinicopathologic studies. The

most consistent prognostic factor is the presence of invasion through

the capsule1-3. In our series we found correlation between DFS and stage

with WHO classification only in cases of thymic carcinoma. This fact

could be explained because of the aggressive clinical course of this

disease.

Few studies have correlated the proliferative index with the

histological type. Chilosi and colleagues32 examined the proportion of

proliferation in 8 cases of thymoma. Using the Ki-67 antigen they found a

large increase in the activity of all examined samples ranging from 35%

to 80% and the expression of this antigen was much higher than that

seen in age matched control thymuses.

These authors speculated whether if this phenomenon might explain the

pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases in these patients. Woo-Ick et al13

found a correlation between PCNA and Ki-67 IP (Spearman coefficient =

0.72). We could not confirm this finding. In summary analysis of a

larger group of patients will be required to determine whether

proliferation fraction as determined by this method can predict outcome.

|

| Figure 4. Actuarial overall survival and disease-free survival for entire group of 22 thymic epithelial neoplasm |

Address. Dr. Hugo Raúl Castro Salguero. Grupo Ángeles,

2da calle 25-19 zona 15, Vista Hermosa I, Edificio Multimédica, oficina

10-15. Telefax: (502) 23857572. E-mail. hugoraulcastro@hotmail.com

Running title. Cell kinetics in thymic epithelial neoplasms

Key words: Thymic epithelial neoplasms, proliferation indices, histologic type, WHO classification

References

1. Loehrer P. Thymomas: current experience and future direction in therapy. Drugs 45(4):477-487, 1993

2. Verley JM, Hallman KH. Thymoma: a comparative study of clinical

features, histologic features and survival in 200 cases. Cancer

55:1074-1086, 1985

3. Lewis RJ, Wick MR, Scheithaur BW, Taylor WF. Thymoma. A clinicopathologic review. Cancer 60:2727-2743, 1987

4. Marino M, Müller-Hemerlink HK. Thymoma and thymic carcinoma: relation

of thymoma epithelial cells to the cortical and medullary

differentiation of thymus. Virchows Arch 407:119-149, 1985

5. Suster S, Moran CA. Thymoma, atypical thymoma, and thymic carcinoma: a

novel conceptual approach to the classification of thymic epithelial

neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol 111:826-833, 1999

6. Rosai J, Sobin LH. Histological typing of tumors of the thymus,

International Histologic Classification of tumors, 2nd ed. New York,

Berlin: Springer, 1999, pp 1 – 25

7. Loehrer P. Current approaches to the treatment of thymoma. Ann Med 31:73-9, 1999 (suppl 2)

8. Masaoka A, Monden Y, Nakahara K, Tanioka T. Follow-up study fo

thymomas with special reference to their clinic stage. Cancer

48:2485-2492, 1981

9. Shimizu J, Hayashi Y, et al. Primary thymic carcinoma: a

clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. J Surg Oncol

56(3):159-64, 1994

10. Ring NP, Addis BJ. Thymoma: an integrated clinicopathological and immunohitochemical study. J Pathol 149(4):327-37, 1986

11. Pich A, Chiarle R, Chiusa L, et al. Argyrophilic nucleolar organizer

region counts predict survival in thymoma. Cancer 74:1568-1574, 1994

12. Pich A, Chiarle R, Chiusa L, et al. Long-term survival of thymoma

patients by histologic patients by histologic pattern and proliferative

activity. Am Surg Pathol 19:918-926, 1995

13. Yang W, Efird J, Quintanilla L, Harris N. Cell kinetic study of

thymic epithelial tumors using PCNA (PC10) and Ki-67 (MIB-1) antibodies.

Human Pathol 27(1):70-76, 1996

14. Pan CC; Ho DM; Chen WY; Huang CW; Chiang H. Ki-67 labelling index

correlates with stage and histology but no significantly with prognosis

in thymoma. Histopatology 33(5):453-8, 1998

15. Gilhus NE; Jones M; Turley H; Gatter KC; Nagvekar N; et al. Oncogene

protein and proliferation antigens in thymomas: increased expression of

epidermal growth factor receptor and Ki-67 antigen. J Clin Pathol

48(5):447-55, 1995

16. Hainsworth J, Greco A. Mediastinal tumors in Haskell M (edd) Cancer

treatment. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Company, 2001 pp 652 – 657

17. Lanfenfeld J, Graeber GM. Current management of thymoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 8(2):327-39, 1999

18. Bernatz PE, Khonsari S, Harrison EG, et al. Thymoma: factors incluencing prognosis. Surg Clin North Am 53:885-893, 1973

19. Baron R, Joseph K, Sagel S, Levitt R. Computed tomography of the abnormal thymus. Radiology 142:127-134, 1982

20. Maggi G, Casadio C, Caballo A, Cianci R, Molinatti M, Ruffini E.

Thymoma: results of 241 operated cases. Ann Thorac Surg 51:152-9, 1991

21. Yagi K, Hirata T, Gukuse T, et al. Surgical treatment for invasive

thymoma, especially when the superior vena cava is invaded. Ann Thorac

Surg 61:521-524, 1996

22. Nakahara K, Ohno K, Hashimoto J, et al. Thymoma: results with

complete resection and adjuvant postoperative irradiation in 141

consecutive patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 95:1041-1047, 1988

23. Caruso ES, Vasallo BC, Beveraggi EJ, Dalurzo L. Quistes y tumores

del mediastino. Análisis de 100 observaciones. Rev Argen Ciruj. 1996 pp:

22 – 30

24. Gawrychowski J, Rokicki M, Gabriel A, et al. Thymoma: the usefulness

of some prognostic factors for diagnosis and surgical treatment. Eur J

of Surg Oncol 26:203-208, 2000

25. Adkins RB, Maples MD, Hainsworth JD. Primary malignant mediastinal tumors. Ann Thorac Surg 38(6):648-59, 1984

26. Okumura M, Miyoshi S, Yoshitaka F, et al. Clinical and functional

significance of WHO classification on human thymic epithelial neoplasms:

a study of 146 consecutive tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 25(1)103-110, 2001

27. Davis RD, Oldham HN, Sabiston DC. Primary cist and neoplasms of the

mediastinum: recent chages in clinical presentation, methods of

diagnosis, management and results. Ann Thorac Surgery 44:229, 1987

28. Wilkins EW Jr. Thymoma: surgical management, in Wood DE, Thomas CR

(eds): Mediatinal tumors: Update 1995; Medical Radiology-diagnostic

imaging and radiation oncology volume. Heidelberg, Germany,

Springer-Verlag, 1995, pp 19-25

29. Hejna M, Habert I, Raderer M. Nonsurgical management of malignant thymoma. Cancer 88(9):1871-1884, 1999

30. Suster S, Rosai J. Thymic carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 60 cases. Cancer 67:1025-1032, 1991

31. Lanfenfeld J, Graeber GM. Current management of thymoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 8(2):327-39, 1999

32. Chilosi M, Iannucci A, Menestrina F, Lestani M, Scarpa A, et al.

Immunohistochemidcal evidence of active thymocyte proliferation in

thymoma. Its possible role in the patho 27:70 – 76, 1996

33. Woo-IcK Y, Efird J, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Choi N, Harris N. cell

kinetic study of thymic epithelial tumors using PCNA (PC10) and Ki-67

(MIB-1) antibodies. Human Pathol 27:70 – 76, 1996

Related publications

- Angeles Medical Group, English Version

- Chemotherapy and side effects

- Clinical Trials

- CRECE english version

- Cáncer de cabeza y cuello experiencia en Guatemala con cetuximab

- Hepatocarcinoma en Guatemala

- Molecular zone, clinical laboratory

- Our services

- Slides and presentations

- Studies in Guatemala

- Types of cancer

- Video conferences

- Who we are